Gestational Diabetes Device

On one fateful night, just four days after her baby shower, on the night she had finished painting the baby’s room, she awoke in a panic. She had become so familiar with her baby’s movement that she was uncomfortable in its absence. In the early hours of the morning, a text message informed me that “baby didn’t make it.” I felt as if an earthquake had shaken my world. Yet, this tragedy opened my eyes to what I wanted to pursue in graduate school: I wanted to use design to help pregnant women.

Wearable technology is a designer’s dream, occupying a place of pride in science fiction. The smartphone embodies the transition from science fiction to reality. Wearable technology changes the way we communicate with one another and the way we exercise, eat, and sleep. I believe wearable technology can have a meaningful impact on healthcare, specifically helping pregnant women with gestational diabetes.

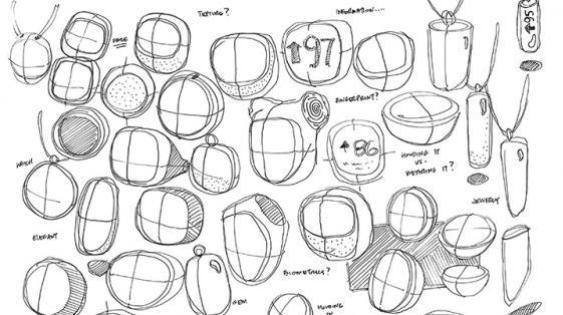

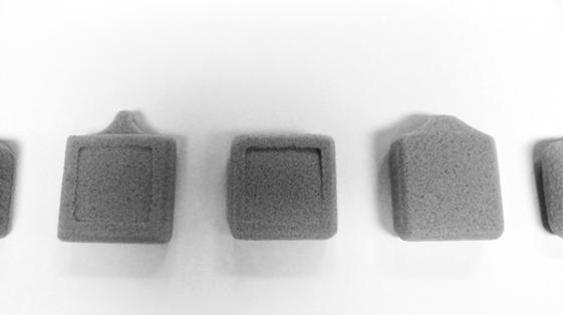

My masters project is a wearable device that can be worn as a necklace or as a clip-on, allowing a woman with gestational diabetes to keep it with her all the time—sleeping with it or setting it on a nightstand to track sleeping patterns. The device notifies her when she should eat and it provides nutritional tips. It indicates when it is time to check sugar levels or to deliver an insulin injection. If the expectant mother has been stationary for too long, the device nudges her to move around. All the information gathered by the device is consolidated and sent to a caregiver. Almost like a smart phone for diabetics, the device is paired with an app that links it to social networks.

The greatest challenge to address for diabetics is their need to constantly check blood sugar levels. To check their levels, they need to draw blood, and in order to draw blood they need to poke themselves. I wanted to provide more discretion for diabetics, allowing them to check their blood in public at any time without feeling uncomfortable or embarrassed.

There’s a stigma associated with diabetes that comes from the need to carry bulky equipment, which can be perceived as a kind of disability. This stigma can be hard to avoid because the diabetic devices currently available have a number of moving pieces and their bulk seems unavoidable. My project minimizes the need for equipment, replacing a finger prick with biometrics, a technology developed by students at Princeton that allows diabetics to check blood glucose levels using a laser.

I began the project as a personal journey in response to the requirements of gestational diabetics, and learned that all diabetics have similar requirements. The final project responds to this more global need. Reflecting the spirit and intent of universal design, the form and function of the final product remains the same for the expectant mother and the general diabetic user.

Designers both posit and answer questions about what the future holds and what the next generation of products will bring. When we consider that the iPhone has more computing power than NASA used to put a man on the moon, we remember that the microchip has brought tremendous change, allowing designers and engineers to bring new ideas to life.

I believe that design for healthcare should focus on understanding and preserving core values of human care while changing practices for durable social and economic benefit. Perhaps technology is not a solution for healthcare, but it can be a supplement.