Translation

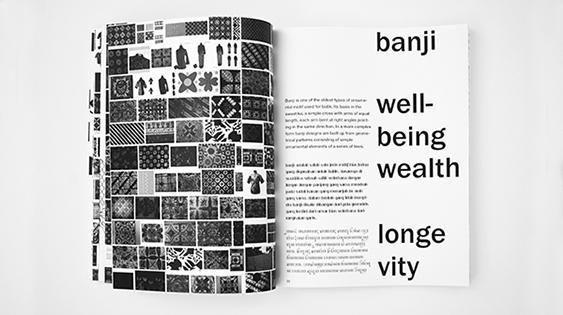

My project centers around Javanese batik—recognized by UNESCO as a masterpiece of human heritage in 2009—and the cultural diversity represented in its diverse patterns, symbolizing Indonesia’s historically complex religious views, cultures, and ethnic identities.

Batik is closely affiliated with the Indonesian people, and more specifically the Javanese who are known for wearing and promoting it. The term batik is an ancient Indonesian word that emerged during the 14th century. During this period, batik meant writing or making a dot or a collection of dots, usually on cloth (Hitchcock, Michael, and Nuryanti, 2000). In Indonesia, batik usually takes the form of patterned woven cloth, created by using canting or a wax pen to cover the parts of the fabric that tend to resist dyeing or color during the process.

Originally localized, batik spread across Indonesia and remains present in most Indonesian communities and at least 18 Indonesia provinces. Today, batik is used to preserve and retain Indonesia’s cultural heritage. By creating solidarity among Indonesians, it allows them to preserve their culture (ibid). Batik has thus gained a reputation as a tool for strengthening cultural heritage and nation building. While Indonesian society contains a broad number of different ethnic groups, their shared connection to batik provides a common visual language to which each group can feel a sense of belonging (Hann, 2013). This sense of belonging plays a significant role in providing cultural continuity, while making a notable contribution to the country’s economy.

Yet while batik has a global reputation, it’s also under attack. Today, simplified formats are designed and applied commercially, and patterns are used without reference either to meaning, or mode of production, jeopardizing batik’s cultural identity.

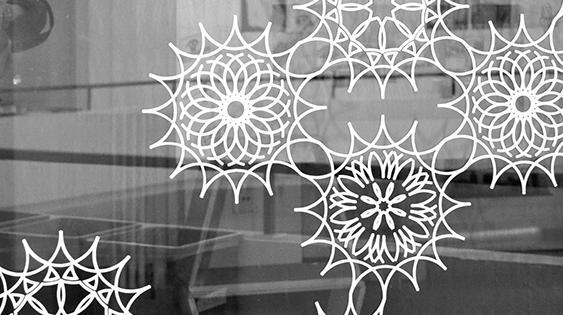

This project investigates alternative materials and more minimalist forms of batik, in an effort to consider batik’s future role and the forms it might take. It consists of six window installations that incorporate three traditional batik patterns alongside my contemporary translation of those patterns. These original patterns were developed in Indonesia’s Buddhist-Hindu civilizations (130–1500 ACE) and Islamic kingdoms (1200–1911 ACE).

The window installations investigate large formats and delicate, cut forms in order to impart information experientially, without being didactic. They represent a form of situational design—design that changes its relationship to users depending on location and context—when placed within this space.

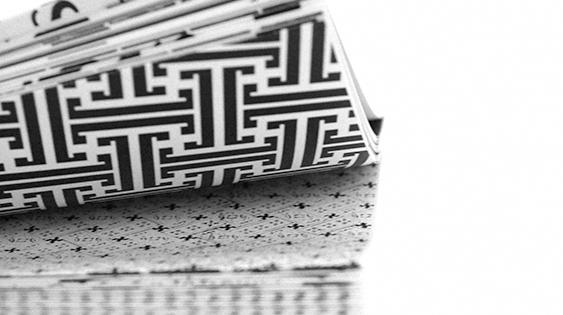

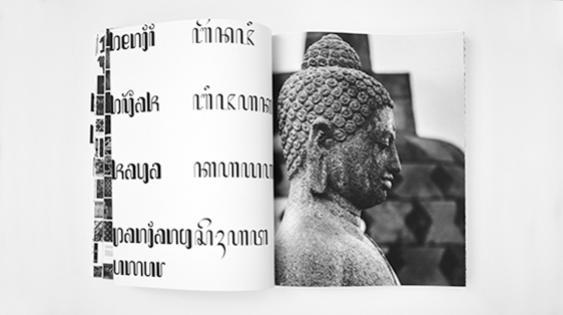

The thesis publication attempts to communicate the meaning behind batik patterns and clarify their cultural and historical context by pairing patterns with photography and texts in Sanskrit, Indonesian, and English. It seeks to visually deconstruct batik in an effort to demonstrate the relationship between these symbols and their meaning.

My interest in batik is driven by a fascination with objects and their ability to represent society. At the center of my interest is the notion of identity. This project serves as a way to recontextualizing local culture within new frameworks. By combining original forms with new formats and media, I hope to develop a hybrid praxis that prompts dialogue.